Yann KWETE, KUB’ART : Identity and transmission. A look at contemporary Art in CONGO.

It all begins with an idea, a dream, but above all a desire. A desire to tell the story of the Congo through the ways of its artists, artisans and trailblazers, those who have something to say. Such is the origin of the journey of Yann KWETE, founder and curator of KUB'ART gallery launched in 2021. Three years on, we discuss about the foundations of this adventure, the art and cultural scene in the Congo, his challenges, and how he has a grand vision for art in Congo. The highlight of AKAA 2023, KUB'ART, whose name is directly inspired by the eponymous ancient Kingdom, is confident in restoring contemporary art in Congo to its former glory. An unfiltered conversation.

Interview by : Ngalula MAFWATA

Ngalula MAFWATA, MAYÌ-ARTS: What is the origin story for your gallery ?

Yann KWETE: My inspiration comes from my ancestral roots, my ethnic group, the Kuba Kingdom, which is most renowned for its immense cultural and artistic wealth through its rare pieces, masks, tapestries and symbols. This is the very essence of my artistic and spiritual heritage. Nowadays, we tend to forget who we are, and my role is to invite the public to think about how to reconstruct our ancestral imaginations in order to preserve our cultural memory. It's an invitation to the reconciliation of an African people with its ancestral culture in a cultural context of globalisation.

"It's important for us to document, to archive, to pass on to a future generation. A people's identity lies in its history and traditions, its spirituality."

Soft Power

I do believe that with a real cultural policy and the right training, we can turn art and culture into significant levers to support the country's economy, in the same way tourism does.

Origins

MA: What is your relationship with the art scene?

YK: I've always been naturally drawn towards hip hop and urban culture. I'm passionate about contemporary art and studied graphic design at Kinshasa Fine Arts school (Beaux-Arts de Kinshasa) before moving into marketing. At the root of my reflexion is the idea that, as Congolese, it's essential for us to be able to tell our story. In the past, we've tended not to take art too seriously, and to neglect its lesser-regarded professions when compared with the classical pathways.

“it is coherent and authentic that today we Congolese or even Africans can tell our stories".

MA: Can you tell us more about your debuts ?

YK: When I launched the Kin-Graff festival in Kinshasa in 2013, nobody understood nor wanted to even be featured there laughs. The irony is that today we can see organisations like the Institut Français organising workshops around graffiti. Graffiti in Africa is all about social criticism, denouncing realities by using public space and murals as conscientious objectors in society. I'd like to think that in some way it has paid off, since we've now been in existence for over ten years.

MA: So was this the genesis of KUB'ART?

YK: It all started back in 2015, when I had the initial idea of working with a cousin to locate and reference across the world all the works of art from the Kuba Kingdom online, through museums and collections. The vision evolved to eventually lead to KUB'ART during Covid with a first digital exhibition. Since then, we've continued to work on other projects, from networking and prospecting to AKAA, international exhibitions and monumental projects at home, mural facades and street installations.

MA: What challenges have you encountered along the way?

YK: We have Congolese artists who are now exporting internationally, but the problem is more structural. There's a cruel lack of interest on the part of the public authorities when it comes to painters, sculptors and photographers, which means that today this movement has difficulty establishing itself in the DRC. We tend to favour other cultural segments such as music and sport, with rumba and soccer. To achieve a society that raises its soft power, all disciplines must come into play. There must be no double standards.

The Congo, a unique position.

MA: And is there any form of evolution?

YK: Yes, there is a big change at the moment, with all the work that has been put in place by local players in the DRC. I have nothing against all those people who came to the Congo before and did remarkable work there, notably Magnin's Congo Kitoko with the Cartier Foundation in 2015. Other players have come to add to the international influence of Congolese art, which means that today there is this visible craze. It's coherent and authentic that today we Congolese or even Africans can tell these stories.

MA: What role does KUB'ART play in this context?

YK: Kub'Art's mission is to highlight contemporary African creativity and showcase the work of African and Afro-descendant artists, in order to contribute to the rise of the scene and make up for previous shortcomings. Fairs such as AKAA and 1-54 have created a real visibility platform for contemporary African creativity, with artists from the Congo, Cameroon, Mali, Senegal and Ghana all managing to position themselves internationally.

MA: If we do compare however the Congo's development with that of its neighbours, there is a difference of pace how do you explain this ?

YK: Let's not forget that the Congo is a continental country with its own dialects and problems. Kinshasa has twenty million inhabitants, Congo one hundred, and we lack space and infrastructures. We need to create events, but we also need the public authorities to support artists, develop national private collections, support collectors... All this will only give more weight to local artists. This requires good will and a certain authority. We need people who understand this aspect, who understand artists and the issues surrounding this eco-system.

An undeniable cultural potential

MA: From your point of view, are there any efforts being made?

YK: To date, artists still don't have a legal status, and the bill aimed at providing them with a better framework has still not been passed (Project presented in October 2023 aimed in particular at legally recognising artists, facilitating their administration among other things, editor's note) We need to resolve these types of problems to start with in order to lay the right foundations. This requires people who are prepared to think together about these fundamental issues, to define the vision of the Congo's cultural policy for the next ten to fifteen years, and to build a real soft power. I do believe that with a real cultural policy and the right training, we can turn art and culture into significant levers to support the country's economy, in the same way tourism does.

MA: Do these groups currently exist?

YK: In silos, just taking my example. Don't underestimate the self-centred considerations, where everyone wants to get the spotlight through their own projects. Laughs. A lot of people tend to work in isolation, compared to other communities if I am being real where collaboration is easy. We don't have that culture yet, and we have to fight against it if we want to see Congolese culture shine. I think it's possible.

Mission

YK: The aim is to highlight the influence of African artists, and Congolese artists in particular, to follow their development and support them. Documenting the work of artists as they go about their work. In the years to come, the second phase of KUB'ART is to set up a private collection of ancient art and present the symbolic elements of Kuba art. The aim is to break the old cycles without losing heritage. Reclaiming the power of narrative. Decolonizing the way we see things.

More than just a gallery, KUB'ART has a mission, as Yann Kwete plans to initiate cultural mediation and better art education through the implementation of programs and activities in the future. On this topic, the founder insists, we need to: "Introduce younger people to our cultures and masks for example, make people understand their origins beyond mysticism in order to contribute to the general influence of art in the DRC. "

Today, we are lucky enough to have institutions such as the Académie des Baux Arts in Kinshasa, which is doing a great deal of work in this area. I think there are people who are better than me who are so keen to show what they're doing, to take action, it's just that they haven't had the opportunities I've had to show this work. There's still a lot of work and effort to be made and support to be given before we really see a radical change, but the will is there. Us diaspora, we can have a positive impact if we unite. It is up to us to change mentalities by traveling back home and setting up activities. Gradually, things will happen.”

End of Transmissions

MA: How does this manifest in the day to day of KUB'ART's operations?

YK: Our mission is to support artists upstream, providing them with all kinds of support, including materials, because it is not always easy to find quality on site. We have also developed Kub'Arts advertising, focused on marketing campaigns and space takeover such as our ongoing project with Hennessy. Multiplying our partners also enables us to take part in fairs such as AKAA (this year AfriCell accompanied KUB'ART, editor's note) and strengthen ties with collectors and art lovers who will follow the gallery. It's also how we meet our future collaborators and partners who could accompany us on this adventure.

MA: This year's fair focused on curatorial practice. How did you set up the project presented?

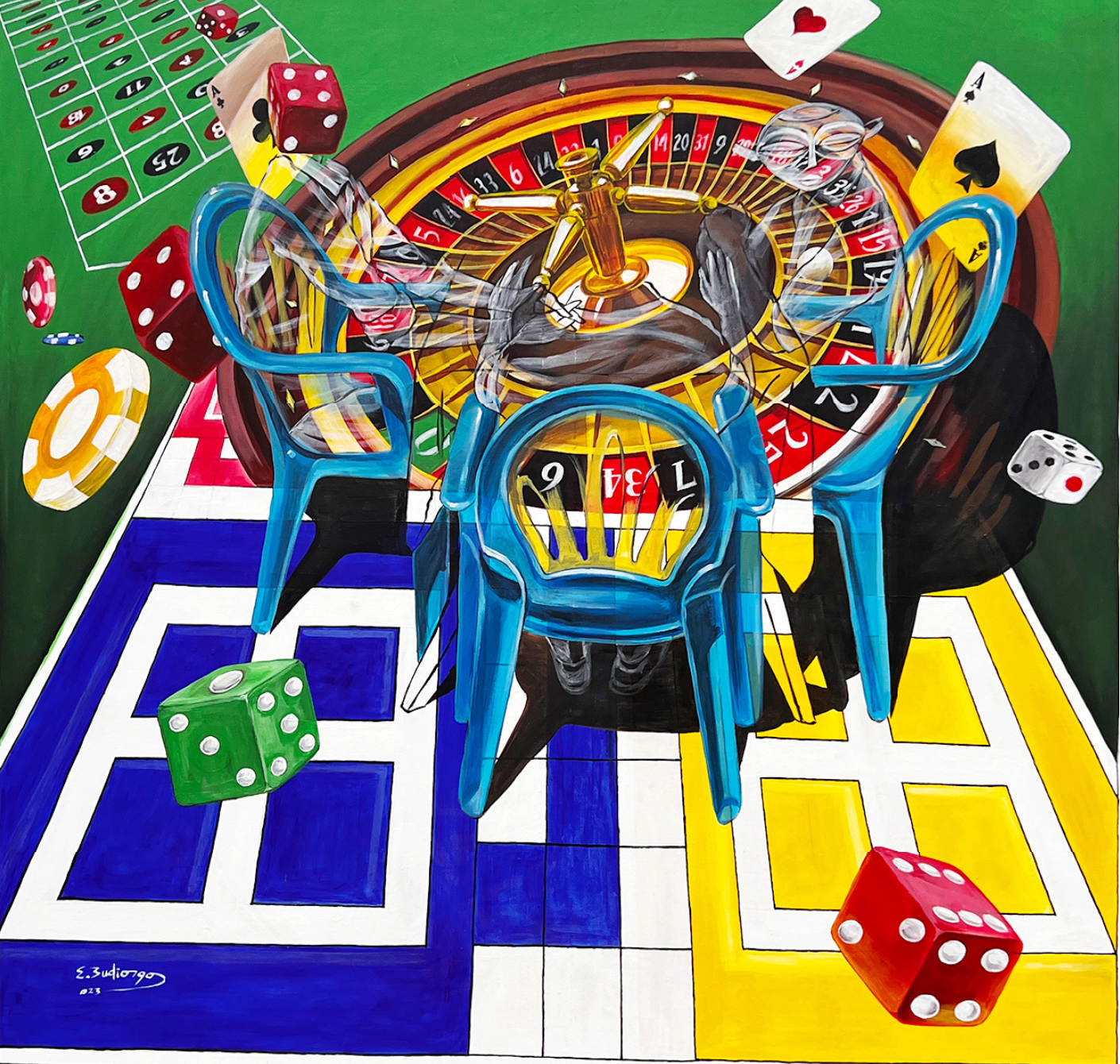

YK: Rachel MALAIKA is an artist with whom I've been working for a long time, in particular the series on ancestral roots, for which we used the collection of my grandfather, a descendant of the Kuba royal family. Prisca MUNKENI, also a photographer, has a particular and raw expression of her emotions that I appreciate. As for Eddie BUDIONGO, we've known each other for years now. I love his work reconnecting the old and the new generations. Together, we set up this project, End of Transmission, which is a long-term project that doesn't stop at AKAA. The project puts the work of these three artists in conversation, and gives us food for thought about how to break cycles without losing our heritage, and how to re-appropriate the existing narrative, freeing ourselves from stigmas. The idea is to set up thematic and curatorial projects that tell a story. Projects that speak to us and are rooted in our cultures, and that we can defend scientifically because they are based on research. It's an approach we want to preserve at KUB'ART. It's rare to see galleries from Kinshasa representing Congolese artists, so there was a certain pride for us.

Source et ressource, Rachel malaika, 2022

MA: How do you see 2024?

YK: Our ambition this year is to keep up the momentum and expand our opportunities according to our means and dispositions. There are also other local projects in Kinshasa with partners, with always in mind to highlight and give our artists the opportunity to showcase their art. With all of this, I am not leaving the urban scene aside either, our annual street art festival will be on again along with a number of other projects that will be taking shape over the course of the year.

MA: To conclude, what are your favorites and talents that we haven't heard of yet and that you'd like to share?

YK: Kinshasa is bursting with talent, and the creative scene is constantly developing. I work with a young muralist, Eliam MUPIPI, with whom we worked a collaboration with Hennessy. There are so many talented artists that it's hard to select just a few, but what really matters to me is the authenticity of the approach, how the artist sees things while looking at his work, and how we can support. In fact, I've limited myself to AKAA. In this way, we were better able to support each artist's development over the long term. It is possible to go beyond what's happening in the Congo, because there are also positive initiatives that we can show abroad. We need to show that yes the Congo has its shares of conflicts, but that this is also a place of creativity and culture.

We must be the ambassadors of this country !