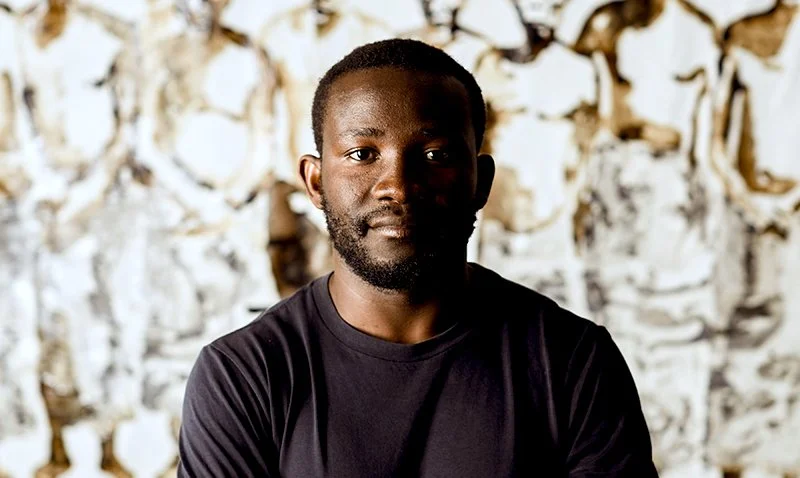

In Conversation : Yvanovitch MBAYA, redefining the African essence in white.

Between dance and turmoil, Yvanovitch MBAYA’s work, focused on movement—of the body, of history— pays tribute to African roots. Ultimately, the individual is but a pretext to explore the rich identity of the African man and an invitation to reconnect with one’s origins to forge a complete identity. Invited to exhibit his work alongside that of the great Master Aboudramane DOUMBOUYA as part of ABLAKASSA’s statuesque project presented at AKAA, Yvanovitch MBAYA retraces the genesis of his artistic journey, driven by a deep desire to discover Africa in depth, starting from Brazzaville, where he grew up.

Ngalula MAFWATA: How did your creative journey start ?

Yvanovitch MBAYA: I grew up in Brazzaville, from a half Angolan mother and a Congolese father. I've always been drawn to drawing, a passion shared within my family: my father was an architect, and my brother, a topographer, also drew extensively. I remember our large illustrated encyclopedia at home, with images of notable figures, scholars, and artworks, which I particularly enjoyed, especially those of the Italian Renaissance. At the end of secondary school, I initially intended to pursue an economic path to honor my parents by choosing a so-called "successful" field. To my surprise, however, my father enrolled me in the Brazzaville School of Fine Arts, where I would begin the following year.

Ngalula MAFWATA: It’s rare for parents to support an artistic career from the start.

Yvanovitch MBAYA: Yes, I actually became aware of this when I arrived in Europe. My father had found a compromise because at the Brazzaville School of Fine Arts, the focus is primarily on training art teachers, which ensured a stable future. At the time, the only place promoting an alternative vision of contemporary art, like that of the Poto-Poto School, was the French Institute.

For Yvanovitch MBAYA, his journey at the Brazzaville School of Fine Arts was one of discovery and study of artistic movements, including Italian Arte Povera ("poor art" born in the 1960s), which sparked a particular passion as it reflected the practice of reusing worn, industrial objects, a prevalent technique among Congolese artists due to a lack of available materials.

"I was already painting and making collages with razor blades. The Fine Arts school allowed me to deepen my knowledge of techniques and art history, exploring the different movements that animate its thread. However, I craved the history of African art, of Congo."

Ngalula MAFWATA: How did traveling impact your work?

Yvanovitch MBAYA: As a rebellious young student, but well aware of my future, I had the opportunity to do an exchange at the Kinshasa School of Fine Arts. Kinshasa is an open-air studio filled with creativity and resourcefulness. I learned a lot about Congolese histories, myths, and traditions there. Lucie TOUYA’s book Mami Wata, the Mermaid, and the Popular Painters of Kinshasa particularly captivated me, prompting me to go to the Kinshasa port to uncover its history; this is how my desire for research began. At the end of my studies, I spent long hours at the French Institute to deepen my knowledge, where I met librarian and comedian Louis MOUMBOUNOU. I sought to assist and support an artist who could mentor me, and he recommended me to the internationally recognized Brazzaville-based artist Bill KOUÉLANY. After an initial rejection, she eventually accepted me as her first assistant. I witnessed the early days of Atelier SAHM Workshops and the launch of the annual gatherings with artists from other African countries. After two editions, I knew it was time for me to explore.

Thus began an African journey for the young artist, who decided to explore the continent’s west to enrich his research project centered on identity, the search for meaning, and the wealth of Congolese traditions and religions. A motorbike journey that first led him to Togo to work in the studios of numerous artists:

"The first artists to welcome me were Tété Azankpo and Sokey Edorh, whose unique works profoundly inspired me. One explored colonial history through materials like bodies, wires, and meshes, while the other focused on the traditional and colonial history of the Dogon people, using pigments and symbolic writing. Being at this intersection of tradition and contemporary exploration nourished my own work and intensified my drive to continue my research. Initially, my journey aimed at studying water, a sacred element in many West African religions, be it voodoo, Mami Wata, or other myths.

This immersion fed my work, allowing me to weave deep connections with traditional beliefs. This process then led me to travel to other countries, encountering myths and traditional narratives, forming the foundation of my work. Then, on April 11, 2015, I decided to explore new horizons, leaving for North Africa. What was meant to be a one-week stay in Casablanca transformed, through the connections I made, into a nine-year journey.

Ngalula MAFWATA: This journey seems to have been formative and influential in your practice as well?

Yvanovitch MBAYA: I was working with acrylics and creating collages when a drop of coffee accidentally fell onto my artwork. I was instantly captivated by the color nuances it created. Intrigued, I thought of skin and earth. West Africa represents Mother Earth, with its many historical exchanges, especially those linked to the Kongo during the deportations of its people. This pilgrimage was my way of retrieving fragments of history, of understanding the influences. Through exploration, I discovered the significance of coffee in African identity, used in traditional practices and as pigment, almost like a drug in the Arab world, where it was once banned by a sultan for its stimulating properties. Coffee thus became a personal element I continue to use in my art.

Ngalula MAFWATA: Speaking of identity, the human silhouette in various positions that you often portray—what does it represent?

Yvanovitch MBAYA: When I was in Congo, I was blind to many things. When people talked to me about ghosts or traditional practices, I immediately thought of black magic. I don't blame the West; it’s just a cultural difference. In our culture, we honor both the living and the departed. My work is built around three dimensions: drawings, suspended cotton canvases, and reclaimed fabrics. My drawings often depict silhouettes. I remember being told by artist Abdelkebir RABI that I was the only artist who could draw Black children in white, capturing their unique essence. This stems from the African tradition where spirits are represented in white. For us, the spirit is not dark or frightening; on the contrary, it embodies the presence of our ancestors. White is a pure colour. In West Africa, for instance, women allowed to pray and invoke the spirits of water and mermaids are called Mamissis. Similarly, in Brazil, women from Bahia hold ceremonies in white garments adorned with beads, a tradition echoed in Vodou practices in Togo, Benin, and Haiti. Red, in turn, features in traditional Ngunza practices in Congo and represents strength and power.

"My goal is to convey identity through a message of universality and to reconnect Africans from Africa and the diaspora."

Yvanovitch MBAYA: Some have lost pieces of their history because they weren’t born on the continent and haven’t yet felt compelled to explore this cultural heritage that’s waiting to be rediscovered. I explore this blend of influences in my work. My art reflects the spirit of identity, inviting everyone to find themselves in a message that primarily speaks to humanity. Nonetheless, I focus on portraying Black bodies, male and female, as they are the references I know best and where I draw my creative strength. Michelangelo, for instance, sculpted the male body with particular grace, which greatly inspired me. I aspire to capture this beauty through perfect lines and curves, retracing silhouettes that tell our story and essence.

Ngalula MAFWATA: Connection between Bantu heritage and spirituality, restoring a lost knowledge base?

Yvanovitch MBAYA: I practiced contemporary dance, which I understand as a confrontation with one’s identity. It's an inner struggle to determine how to position oneself, to move, to occupy space and bring it to life. I had the chance to work with two dancers, Aipeur FOUNDOU, known as the "God Dancer," and Dethmer NZABA, who combines elements of Ngunza traditional dance and Japanese Butõ, with its focus on lyricism. Ngunza dance is driven by trance, the Mpevé, where the spirit and body speak together, highlighting the significance of words in this practice. Bantu religions teach the importance of roots, ancestors, and gods. There is the God of the West and the God of Africa. I believe in a single God, the creator of all things, even if our ways of invoking this God differ. My work sheds light on our traditions and ways of connecting with our deities. This is represented through postures merging Bantu practices and Japanese Butõ, as I see similarities in our rituals. I am convinced that our practices connect us as ancestors to the Asian people. I study Butõ movement photos and draw inspiration from their work. My art is about remembering and fostering cultural exchange.

Ngalula MAFWATA: Speaking of impact and reception, Bichi Kongo is a notable work—what is its origin?

Yvanovitch MBAYA: This piece is unlike anything the Parisian art scene has seen. I intentionally used a reclaimed fabric, with its own story, to add history. The figures depicted come from an archive photo. Bichi Kongo brings forth faces of the past, from the colonial era, showing their strength, deeply rooted in their traditional practices. Their intense gaze creates a strong connection between me and the material. This piece uses a mix of pigments, coffee, charcoal powder or burnt wood, Indian ink, and indigo pigment, which I discovered in Mali in 2019. This work embodies self-acceptance and identity. A complete person is one who asserts their identity, declaring, "I am an African artist; I value my culture." This piece is a declaration, a weapon for cultural expression. In each of my exhibitions, I like to include a piece made on reclaimed canvas to say thank you to my ancestors, as it’s thanks to them that I am here. At the same time, I create a ceremonial universe and ancestral practices that invite the public to witness who they were and how they honoured their culture.

Ngalula MAFWATA: ABLAKASSA is a significant project at AKAA. Can you tell us about its origins?

Yvanovitch MBAYA: I consider myself fortunate enough to be invited to this project. Last year, I presented Gâta Bantu (One Village, One People) at 1-54 Marrakech, where I met independent curator Roger KARERA. Alongside Jean SOMIAN SERVAIS, they initiated ABLAKASSA.

The project was born, inspired by the legacy of Bisi SILVA (1962-2019) ‘ s philosophy to counter the almost obsessive need to be accepted abroad rather than building the local scene. Not exhibiting in Paris doesn’t mean the end of everything. As Ivorians say, I don’t put sand in my attieké; recognition does exist in France and Paris. However, we must also recognise the opportunities Africa offers today. Without taking anything away from artists in the West, today, an African artist living in Africa has many stories to tell in contemporary art. The African art market is strong now. Fairs and events such as Art x Lagos, Investec Cape Town, or the Dakar Biennale showcase incredible stories through the artists featured. We've always used elements from nature and daily life to create our works. I even believe the founding figures of the Arte Povera movement must have traveled to Africa upon creating it.

Jean SERVAIS and Roger KARERA had the vision to put under the spotlight all these great and already complete artists who only lack the visibility to reach new heights. The first ABLAKASSA edition took place between Abidjan, Assinie, and Grand-Bassam, where several artists from the continent and the diaspora, myself included, exhibited across different venues. The second edition was at the Donwahi Foundation in Abidjan AKAA came as the third leg of what started in Africa. It was a way of showing the world who we are and how our work evolves. Master Aboudramane DOUMBOUYA is central to the curation, and as a young artist, I was invited to respond to his work. I first encountered his work in 2014 in Lomé, while assisting the German gallerist Peter Herrmann, who introduced numerous artists working in Africa in the 1990s. Visiting his studio, I was captivated by his work, his story, and saw myself in his approach as an African artist. For the AKAA exhibition, I imagined performing figures within his mini-temples to create a connection with his work. I am truly honoured to participate in this project with Jean SOMIAN SERVAIS, Roger KARERA, and Mary-Lou NGWE SECKE. Promoting African artists in Africa and the diaspora, especially young artists based in Africa, is crucial.

Ngalula Mafwata: It's fascinating to see all the connections being built among African artists and the diaspora, collaborating to reclaim the narrative. As an African in the diaspora, I believe it’s essential for us to take action on the continent. What is your view on the Brazzaville art scene?

Yvanovitch MBAYA: I will be straightforward, as teaching demands it. I’ve visited 37 African countries since I was 12, traveling by foot, by motorbike, sometimes without my parents knowing, because I had a thirst to explore the continent. Africa is a land of oral tradition, and I learned so much by traveling and meeting people. Unfortunately, young painters in Congo aren’t working as they used to, and I know the reasons why, though I won’t use political terms. Let me just say that the Ministry of Arts and Culture in Brazzaville doesn’t do enough to support artists. It’s not my role to contact them; it’s their role to be interested in our situation. I’m often the only Congolese artist present at any international fair or event I participate, as we lack infrastructure in Congo. Aside from Atelier Sahm workshops and the French Institute, there are few other exhibition spaces. Baudouin MOUANDA’s ClassPro Culture project is one of the rare personal, committed initiatives.

The standard has significantly dropped because artists are less active. There used to be competition between artists, pushing us to excel creatively rather than copy each other. I encourage the diaspora to come to Africa, to buy works, to motivate artists, as funding remains a major problem. Many of them work in default professions, like accounting, even though their true talent lies in art. Today, we see artists from Benin and Côte d'Ivoire represented in Venice, yet few Congolese artists are recognized internationally to the point of establishing a pavilion. There are only five or six currently, due to a lack of resources and representation to create works and get artists to travel. At the AKAA fair, only two Congolese artists were present: Gastineau MASSAMBA and myself.

Obtaining a talent visa is difficult, especially for those without a strong CV. The lack of support limits artists' ability to exhibit, especially at major events like the Dakar Biennale. If we lack the opportunity to exhibit in Brazzaville and the funding to support our work, the journey becomes even more challenging. The Dakar Biennale scene benefits from Atelier Sahm workshops, but it remains insufficient. I’m not claiming my work is the best; I’m still a young artist in development. My success at AKAA is thanks to the people who supported me, but those people, truth be told, aren’t Congolese. I’m grateful for their help, yet we lack state infrastructure and support, like repurposed factories serving as studios with essential equipment.

This is an ideal time to act, as there’s heightened interest in African art on the market. We can’t miss this opportunity, especially with emerging markets like China. Congo must create a pavilion for the next Venice Biennale, and we, the artists, are ready.

Ngalula Mafwata: In the Francophone world, we have models of excellence like Benin with its Agency for Art and Culture Development.

Yvanovitch MBAYA: What Benin is doing is incredible, highlighting the importance of civic engagement. The President appoints qualified individuals to oversee culture and organise outstanding exhibitions, like this pavilion showcased in Paris that invites both established artists and the new generation. He even showed up unannounced to support this initiative, recognising his citizens' commitment. We must follow this example. Our President isn’t very visible, as cultural leaders don’t fully engage. It’s not the President’s job to handle these responsibilities. Our Minister is doing her best; she recently attended a Roga-Roga concert but was booed by the diaspora, which is unfortunate. I do see efforts from our ministry, including an online presence. We, on our end, need to encourage these efforts. Artists need to work, propose projects, and the ministry and cultural stakeholders must support them.

We have a rich artistic heritage with figures like Bill KOUÉLANY, Remi MONGO ETSION, Marcel GOTÈNE, and Gastineau MASSAMBA, they too deserve national representation at the Venice Biennale. If we’re invited in ten or fifteen years, it doesn’t matter, as it would mark a beginning. I also want to acknowledge Benin’s initiatives in this field.

Ngalula Mafwata: What projects or studies are you currently working on?

Yvanovitch MBAYA: I have a dream [laughs]. Until now, I’ve often avoided addressing certain politically charged topics. Jean-Michel Basquiat claimed that Black people were underrepresented in modern art—a message that, unfortunately, was often misunderstood. Inspired by this idea, I want to continue my work on identity. As a Congolese person who left my country to better understand myself, fully embrace my culture, the historical past of my continent, and accept who I am, I seek to convey this journey through my art.

Find the work of Yvanovitch MBAYA on Artsy, Foreign Agent and on his personal spaces.